Coming back to Nice recently after a glorious two weeks in South Africa, I thought about my bizarre, dual existence. On the one hand, there’s my heritage – bold, earthy and abundant – and on the other; the subtle, refined and restrained Frenchisms I’ve adopted, especially as a chef. Which led me to wonder: If I had to express this duality through food, what would it look like? Is it that I sometimes miss a dash of cinnamon in my flan? That I feel some things need to be slightly burnt to enhance the flavour? In my mind, the souttert (savoury tart) and the quiche have engaged in a cross-cultural battle since the birth of the souttert. Most South Africans don’t know the difference – and don’t feel they need to. After all, why limit your options? Anything goes, right? Of course, the French are very quick to point out that a souttert is definitely NOT a quiche. And I have to say I agree. But I for one am also quick to point out that a quiche will never be a souttert. But this is not a competition. Both hold a very special place in my heart.

According to my dear friend, Errieda du Toit – one of the foremost authorities on South African food – the souttert stems from tradition, like so many of the classics. “It is customary to bring a plate of souttertjies (small savoury tarts) to a church function. It’s a way of showing that you’re pulling your weight, that you’re contributing to the endless array of tidbits causing the tables to buckle on such occasions, whether at a cheerful baptism or a sombre funeral. When in doubt, bring one plate for prayers and two for goodwill,” she says, adding, “No one is told what to bring and no one is expected to bring anything extravagant or exotic. Rather just a variety of familiar tastes.”

To the quiche-prone French, however, there is something, shall we say, outlandish about the copious amounts of ingredients we use in a souttert, from the crust to the filling. Like frittata, the souttert filling provides you with an opportunity to repurpose your leftovers. I’ve also had it with bully beef, curry, and even sliced Viennas more times than I can remember. Yes admittedly, we South Africans love an abundance of flavours and textures, so why hold back?

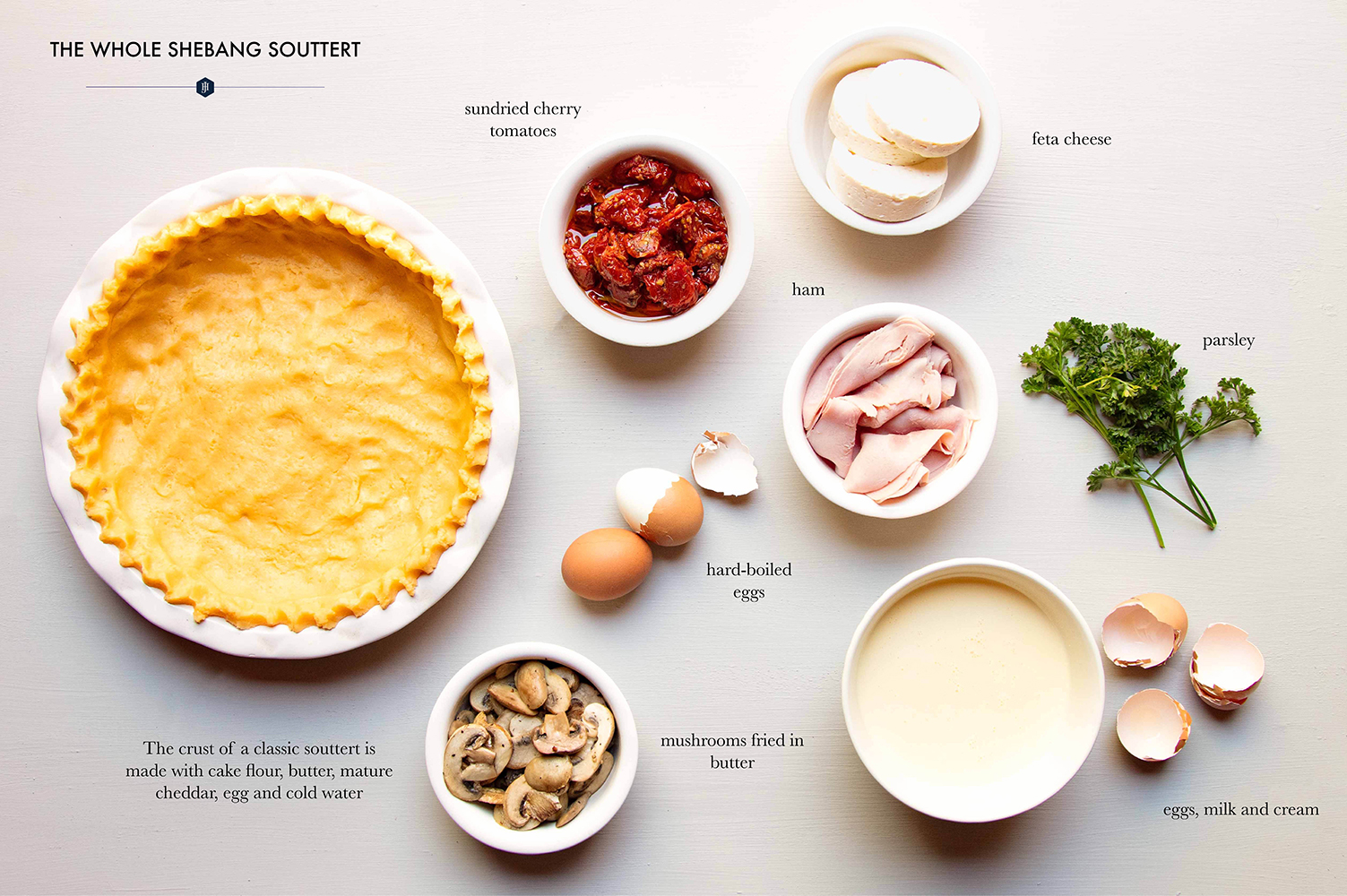

The whole shebang souttert

INGREDIENTS

pastry

140 g (250 ml) cake flour

2,5 ml baking powder

75 g (80 ml) butter, at room temperature

240 g mature cheddar cheese, grated

1 egg, beaten

15 ml cold water

filling

15 ml butter

250 g mushrooms, sliced

3 wheels of feta cheese, crumbled

20 sundried cherry tomatoes

10 slices of ham, diced

3 hard-boiled eggs, sliced

3 eggs

125 ml cream

125 ml milk

handful of parsley, finely chopped

freshly ground black pepper

METHOD

pastry

Preheat your oven to 180 °C. Place all the ingredients of the pastry in a food processor and process until a pastry forms. Spray a 23 cm tart dish with non-stick food spray.

Press the pastry into the tart dish. This pastry is so soft that you can’t roll it out with a rolling pin.

filling

Melt the butter in a pan. Add the mushrooms and fry until soft. Remove them from the pan and let them cool.

Sprinkle the crumbed feta on top of the pastry. Arrange the mushrooms, cherry tomatoes and ham on top, and finally; the hard-boiled egg slices.

Beat eggs, cream and milk together and pour the liquid over the filling. Sprinkle the parsley on top and season with black pepper.

Place the uncooked souttert in oven and bake for 45 minutes to an hour. Remove and let it cool for about 10 minutes before serving.

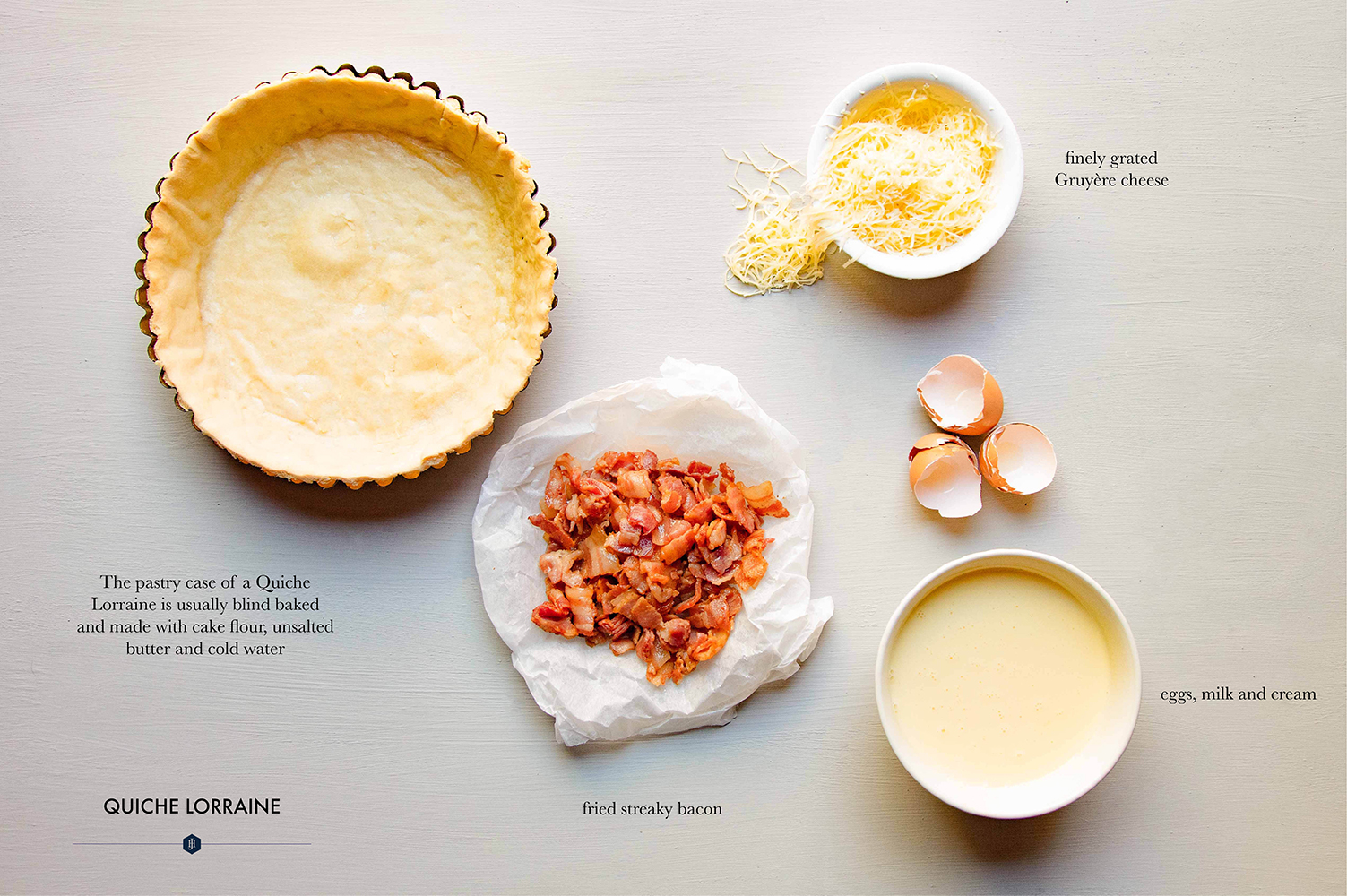

In its purest (or purist) form, quiche is a flan-like savoury tart filled with eggs, milk or cream. As with any custard-based tart, the filling becomes a platform on which to showcase a variety of ingredients, such as seasonal vegetables to meats and seafood. The crust is almost invariably blind baked (see below) and lined with a generous layer of grated cheese, like Gruyère. When I first had a quiche in Paris, it surprised me how much deeper it was compared to the savoury tarts I’d always loved and known, so the slices generally tend to be thinner. And without fail, a quiche is made in a loose-base fluted quiche tin in France. I’ve always looked at Quiche Lorraine as Queen Lorraine: queen of the quiches, and this recipe is the one to beat.

Quiche Lorraine

INGREDIENTS

pastry

300 g (535 ml) cake flour

150 g (165 ml) unsalted butter, cut into small blocks

80 ml cold water

filling

20 ml olive oil

500 g streaky bacon, diced

200 g Gruyère cheese, finely grated

6 eggs

500 ml cream

250 ml milk

freshly ground black pepper

30 ml chopped parsley

METHOD

pastry

Place the flour and butter in a food processor. Process until the mixture resembles fine bread crumbs.

Add water spoon by spoon until a pastry forms. Take the pastry out of food processor, wrap it in wax paper and let it cool in the fridge for 20 minutes. Preheat the oven to 180 °C.

Roll the pastry out onto a lightly floured surface until it has a thickness of 2 mm and line a 23 x 5 cm loose base fluted quiche tin with the pastry. Spray the tin with non-stick food spray before lining it with the pastry.

Blind bake the pastry (see below)

filling

Heat the olive oil in a pan. Add the bacon and fry until crispy. Drain it on a kitchen towel.

Sprinkle the grated Gruyère cheese in the blind baked quiche tin. Sprinkle the bacon on top of the cheese.

Beat the eggs, cream and milk together in a mixing bowl and season with black pepper. No salt is needed – the cheese and bacon is salty enough.

Place the quiche tin on a baking tray and pour the egg mixture into the quiche tin. Carefully place it in the oven and bake for 45 – 55 minutes. Make sure the egg mixture / custard is set. Take out of the oven and let it rest for about 10 minutes before removing the quiche from the tin.

how to blind bake a pastry

By partly cooking the crust before you add the uncooked, liquid filling, you prevent the crust from becoming soggy when you bake the quiche. I always keep a jar of “baking beans” handy that I use again and again. I actually have no idea how long I’ve had them, come to think of it, but whatever you do, don’t cook and eat them.

Line your quiche tin with rolled-out pastry, allowing the pastry to drape itself freely over the edge of the tin. The reason for this is to prevent the pastry from shrinking.

Place a big piece of baking paper over the pastry and fill it with dried beans.

Place it in the oven and bake for 10 minutes. Remove it from the oven, lifting the baking beans out of the pastry case and pouring them back into their special jar. Cut the excess pastry off with a sharp knife.

Prick the pastry slightly with a fork and brush the bottom with beaten egg white. This will prevent the pastry from going soggy.

Place it back in the oven for 5 more minutes. Take it out and let it cool before adding the filling.

FEATURED RECIPES